Reverse Shot: Approaching Mozambican History.

1 Aug, 22

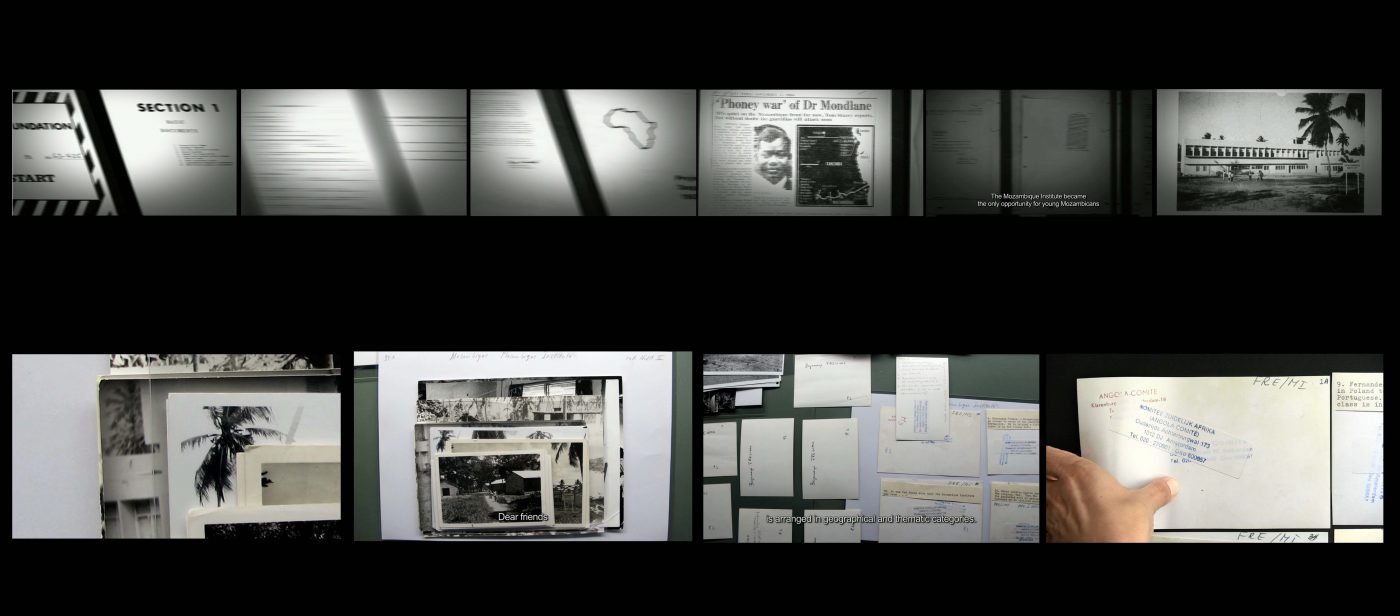

SB: In Effects of Wording, there are several different political strata. The film begins with big politics, with a parade of microfilms of letters, articles, and reports that unveils the political-economic stakes of the first educational project created by the nationalist independence movement in exile, the Mozambique Institute, on an international scale. In particular, it captures the complex intricacies of disparate elements such as the Cold War, the issue of decolonization, debates on which strategies to adopt, and so on. But very quickly, the film changes scale, and you begin looking for signs in the images of a different politics, a politics that is not subsumed under big politics and that is expressed through bodies, gestures, ways of doing and saying.

[1] It was across the border from Mozambique, in Tanzania, that conditions for a new generation of Mozambicans pursuing their studies were idealized, and where a new pedagogical system was founded, in rupture with the colonial system. Soon after 1962, and while the armed insurrection was being prepared, the first president of FRELIMO, Eduardo Mondlane, raised funds together with international donors, for the construction of this school, the Mozambique Institute. The first support was provided by the American Ford Foundation, which made its first year of operations possible, just before being forced to discontinue the support due to Portuguese diplomatic pressure.

CS: The center of my film is there, in the images that seem to be obvious but are not. This was also the trigger of the film: Effects of Wording was born when I came across images in the archive that I did not quite understand. They were images of 1967, shot in Super 8, without sound, and what we saw were daily situations that took place in an educational establishment called the Mozambique Institute[1]. These were images that seemed to have no connection to the war and to be unrelated to the colonial Catholic schools. To understand them better, I interviewed the author of the images, who explained some details to me. There were situations that might have seemed trivial, such as that of the young people washing their laundry, but in fact they bore a very important element of emancipation: these people were taking charge of their lives. They felt responsible for themselves, which was a step out of colonialism, whose constant discourse was that it was indispensable to be guided by a white who knows best and who protects. There was, therefore, in these images, another stratum to be unfolded, that of daily practices, which were very important in the context of liberation. So I found that these images required one to be attentive to these small details, which show that what seemed personal and daily had in fact a strong political content, even a militant one.

It was across the border from Mozambique, in Tanzania, that conditions for a new generation of Mozambicans pursuing their studies were idealized, and where a new pedagogical system was founded, in rupture with the colonial system. Soon after 1962, and while the armed insurrection was being prepared, the first president of FRELIMO, Eduardo Mondlane, raised funds together with international donors, for the construction of this school, the Mozambique Institute. The first support was provided by the American Ford Foundation, which made its first year of operations possible, just before being forced to discontinue the support due to Portuguese diplomatic pressure.

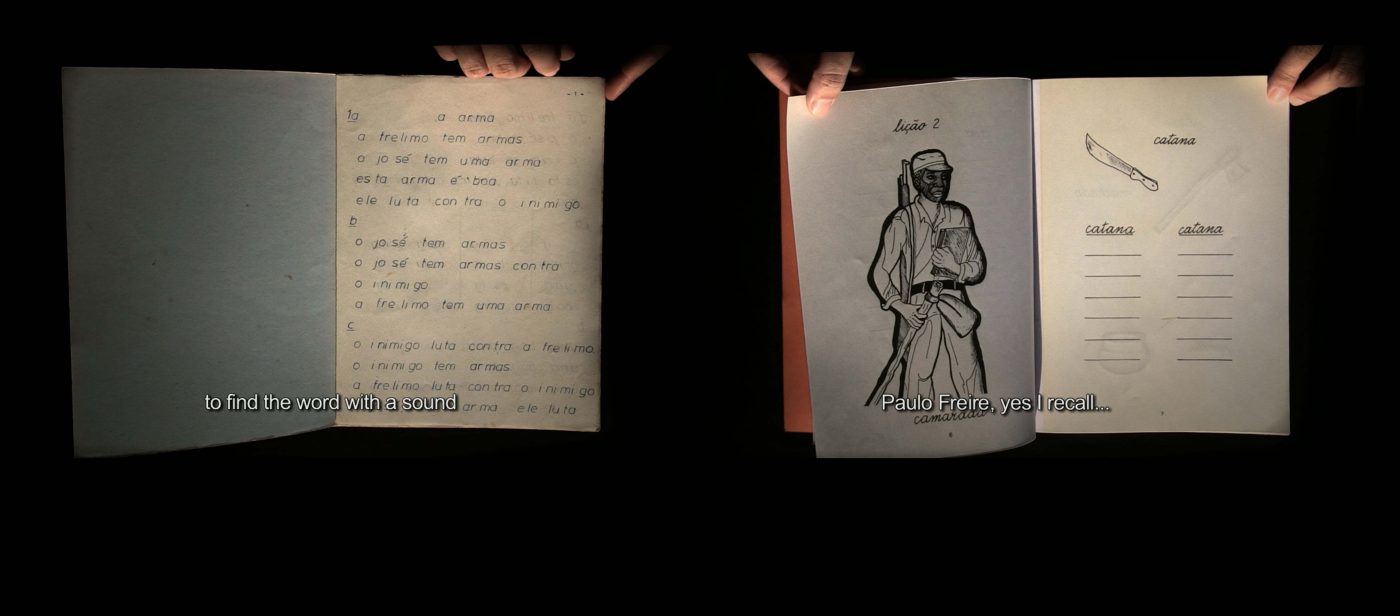

SB: The main theme of the film, which is already mentioned in its title, is the problem of language, namely the problematization of the alleged neutrality of the colonizer’s language and its various active reappropriations by the liberation movement. FRELIMO[2] opted for Portuguese over the indigenous languages that existed in Mozambique at that time, to avoid ethnic conflicts, quarrels between communities, and so on. But the Portuguese that it spread was different from the one spoken in Portugal. Do you feel that, in your work, you are learning another language?

[2] FRELIMO, the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique or Mozambique Liberation Front, has been the dominant political party in Mozambique since the country’s independence in 1975. FRELIMO began as a nationalist movement in 1962 and engaged in a ten-year struggle against Portuguese troops for the independence of what was then called the Portuguese Overseas Province of Mozambique

CS: I certainly feel now that I have a more critical look at my mother tongue and its influence on one’s thinking and self-image. There was no critical work, for example, on certain terms that were used strategically during the dictatorship, when the colonies were still considered Portuguese territory. The word explorar, for example, means both “exploring” and “exploiting,” unlike its equivalent in other Latin languages. Rada Iveković, who contributed to the project, made me aware of this. Thus, the Portuguese language uses the same word to designate that which belongs to the adventure, to the discovery of the unknown, therefore relating to something liberating, and what belongs totally to the capitalist and imperialist register. This confusion operates as a definition of the discoveries themselves: there is this double dimension that has never been dissolved. It seems that in our collective unconscious, exploring something requires that we exploit it at the same time. Another example is the Portuguese word for engaging, comprometer, which also means to compromise oneself. In Portugal, one does not use the Brazilian word, engajado (engaged), to differentiate between the two.

SB: Apart from the question of language, the relationship between Portugal and its colonies is also complex at other levels: on the one hand, Portugal was colonizing, exploiting its colonies and waging a bloody war against them, and on the other hand, at least in Mozambique, Samora Machel [3] always said that not only should Mozambique be liberated from the Portuguese colonizers, but also the Portuguese people should be liberated from their dictator and from fascism. There was therefore a certain solidarity with the oppressed people, beyond the question of nationalities.

[3] Machel became the head of FRELIMO after the assassination of Eduardo Mondlane in 1969 and was the first president of Mozambique. President Machel was killed in a plane crash in 1986, in Mbuzini, South African territory.

CS: Yes, it was a propaganda speech by FRELIMO, with a very clear purpose: to convince the Western capitalist countries, through a liberating, anti-fascist discourse, to support them, since they were not terrorists or savages, as the discourse of the Portuguese regime suggested. This propaganda also included other dimensions, such as the liberation of women, the idea that prisoners of war would not be killed—in short, the idea of a strong solidarity between peoples, which would be upheld against violence, etc. This very intelligent strategy was highly successful, and its repercussions on the writing of history are remarkable and often a bit paradoxical: certain statements appear in archival documents as truths, when they were actually strategic elements of propaganda. At the same time, other events, such as the internal conflicts within the Mozambique Institute, which was a major crisis affecting the movement and which ultimately led to the assassination of Eduardo Mondlane[4] in 1969, are kept in silence, and it is difficult to find traces of them in the archives.

SB: In your work, research has a very important place. You spend a lot of time in the archives, you study a lot of documents, and you talk with a lot of people. In a way, you try, at first, to penetrate into reality as a historian would. But at the end of the day, you always come back to the images themselves, to mobilize what appears on their surface against accepted ideas, but also against learned appropriations that cut them off from their expressive force by submitting them to external categories, academic reasonings, or Eurocentric readings. It is as if the images you find in the various archives (in the United States, Sweden, Portugal, and Mozambique) allow you to circumvent their own myth, their inscription in a corpus, and their classification.

CS: These myths and categorizations add a layer to the way we understand documents. That is why archives interest me, not only for their content, but also for how they are organized, how they classify and arrange their collections, and how they produce a working environment. In Effects of Wording, I avoided locating the materials that appear in the film, but there are visual effects that refer to specific places. For example, at the beginning of the film, there are microfilms that come from the Ford Foundation Archives, which itself is part of the Rockefeller Foundation Archives in the United States. It is a kind of palace, very well organized, very efficient, and a little overwhelming, which is quite fascinating. At the same time, this efficiency also evokes a sense of being before incontestable facts.

SB: In archives such as those of the Ford Foundation, one remains motionless while consulting the documents, in a very comfortable chair. An archivist brings you what you asked for, and from there a knowledge or a narrative is built. In the archives in Mozambique, you search for things yourself, dust off video tapes, decipher the handwriting and its meaning.

CS: Yes, working with the Mozambican archives requires much more effort, whether in the relational or in a physical sense, and an intelligence other than the rationality of making sense of documents that are well organized and already at my disposal, of which I may decipher the meaning, perhaps sometimes between the lines, but which is clearly before me, readable and accessible. At the same time, the documents found in these American and European archives are sometimes more problematic. For example, in the US archives, FRELIMO members in exile in Tanzania are often referred to as refugees. They were not refugees, but to designate them as victims could justify supporting them financially. Mondlane, for example, was very diplomatic and well versed in obtaining financial support from the Ford Foundation.

SB: This shows at the same time how the denomination is useful, effective, almost performative. Mondlane adopts the language of the Americans, presents his project as humanitarian in order to access funds, and archival policy follows this path by applying the same words to its categorizations, thereby inflecting documents in the direction of propaganda.

CS: That’s why I try to present documents that are found in very different and distant archives that show disparate facets of the same issue, all of which hold some part of truth. Working in the Mozambican archives poses different problems from those found in the Western archives. Many documents have been lost or damaged, video tapes are nothing but corpses, the only thing that remains is the title that was given to them. They are, rather, objects, relics. What I do is take a photo of them, hoping to discover something unsuspected afterward, when coming across them with new knowledge. There is always a back and forth between the things I see and the things I learn. The most important experience for me lies in this process, and I always try to come back to the moment when it was still new to me, to find the enigma of a word, of a film sequence, or of a photo that I did not yet understand and that becomes another thread for me to weave.

SB: So, for you, the experience you make, the efforts to understand better, the pursuit of the signs that you discover, fills the image with different dimensions, like a prism. But from these layers of knowledge, you return to the image to see it differently than as a container of information. What interests you is therefore the dialectic between knowledge, information, on one side, and the being-image that refers to something else. It seems to me that this dialectic between the sensible and the intelligible becomes tangible if one looks at your two films Effects of Wording and Ntimbe Caetano together: whereas the first film works much with words, evoking many different registers of the historical sense and its actualization in the present, the last film contains very few words and concentrates instead on the movements of the bodies, the gestures, the rituals. It is as if we should now find the counterpart of knowledge, the way in which a past is inscribed in bodies, how it forms a memory and produces gestures.

CS: Yes, absolutely, I consider them complementary. In fact, Ntimbe Caetano was even conceived as a response to Effects of Wording. The curators of the exhibition Fevered Specters of Art had asked me to do a kind of sequel to it, and I suggested something more experimental, a kind of reverse of words. I realized that it was not easy to capture the violence and inherent ambiguities in what is said in Effects of Wording, and I wanted to reinforce this aspect in the new film.

SB: Looking at Ntimbe Caetano in relation to Effects of Wording, I found it striking that you are clearly in the present, a present that appropriates the past, that expresses memories, without resorting to archival images or information other than that which is said by the people with whom you work. You situate what is seen even less, even if it is sometimes implicit, as in the scene of the massacre of Mueda [5] which is reconstructed with figurines in a museum. But the access passes through the body of the guardian of the museum, who, instead of telling, makes a kind of dance with his hands, touching the window, pointing and searching. The other gentleman you film taps his foot on the floor, and other scenes show a ritual dance. In Ntimbe Caetano, everything seems to pass through the body, the rhythm, the gestures. As a result, the question of the viewer and of their position arises differently, because you give very few pointers in this film. There are many repetitions, an almost hypnotic soundtrack, which evokes remembrance rather than information.

The massacre at Mueda in 1960 was one of the events that motivated the liberation movement in Mozambique.

CS: Yes, I wanted to emphasize the difficulty of understanding and the differences between the construction of a narrative and the traces that are imprinted in the body. The representation of the Mueda massacre is important to me also because here it is not very common to think that the colonized also represents the colonizer. When you live in Mozambique, you realize that these representations are everywhere, and they are fully integrated in life: they are in songs, in movies, and in the way people speak, but maybe this is sort of evident. The film by Ruy Guerra (Mueda, Memória e Massacre (Mueda, Memory and Massacre), 1979) replays a little this ignorance of the European who is too fixed in this idea that it is he who is able to represent the black person, and not the other way around.

SB: In the Ruy Guerra film, representation goes through incorporation, in this case by Mozambican actors who play the whites, often ridiculing them. Classical Western representations often show the colonized as an other, an object to be contemplated from afar. In this distancing there is a power, that of excluding and dominating the other. Whereas in Mozambique there is no such distance, since the colonizer penetrates into life and does not allow himself to be dismissed, and so representation goes in another way, through an incorporation, a becoming, an appropriation that transforms. It’s much more performative when you re-enact a scene, when you put yourself in the skin of the other instead of making them an object.

CS: And the role that they are playing is so well known, the presence of the Portuguese so enmeshed in the everyday, that they can add a layer of humor, of cynicism.

SB: What you do in your work seems to me to be something other than the representation from afar of the European or the incorporation of the African. I have the feeling that you are putting us in this situation where it becomes perceptible that there are things we do not understand.

CS: I think that being able to study something at a distance, temporally and geographically, an intricate, complex, very charged story, is what makes it impossible to access certain layers that are, however, important for understanding. This idea that knowing how to read allows you to penetrate into a sensible thing is already part of the problem. When I tried to understand the images I spoke about at the beginning, I thought I had grasped them, but it was difficult not to project knowledge. There are things that had to be rediscovered differently, by forgetting what I knew and going beyond my categories. When you touch such materials that have not been directly associated with a written history, you have to see everything, rethink everything, understand the situation in which it was made, in its difference with our own projections.

SB: In Effects of Wording, there is precisely this idea, that nothing in language is neutral. Neither that of the foreigners, which imposes a logic that does not quite grasp lived experience, nor that of the Mozambicans, who know the subject from within, by experience, and who make of it a tool for emancipation. With the idea that some possess the true language with which certain things cannot be said, there is the idea of violence. But in order to approach this subject, it is necessary to resort to written and spoken language. In your film about language, you chose English. Your accent adds another layer, because we become aware of strangeness and distancing. This small gap introduces a small break in the film. We understand you very well, we follow you, but there is something that does not quite fit—the heterotopic moments, as Michel Foucault would have said. The same words do not necessarily mean the same things.

CS: That’s true, but in the version I did to show in Mozambique, it’s me speaking in Portuguese. It made sense for me to speak in this language that I share and do not share with the audience. In fact, it was in Mozambique that the film took on its most correct meaning, because there were repercussions, consequences, research that began over there, about the Mozambique Institute, which was not very well known because of confusing political situations. On the other hand, I have learned a lot through the meetings I have had, with people involved in one way or another with the institute and the professors there who work with the making of textbooks. So in Maputo, people recognized things in the film, the drawings in the books that they studied when they were children, the small details—these are very personal things related to the memory of childhood that arose and which have taken a biographical perspective. This is completely foreign to me, of course; I cannot link these images to anything directly personal, to an experience of struggle and my own self-construction.

SB: So you made your film thinking of the Mozambicans who would see it rather than the Europeans?

CS: Yes, I think so. I do not really have a clear picture of the Mozambican audience (if it exists), but I certainly think of the Mozambican historians and activists that I respect very much. When I did the editing of Effects of Wording, I already knew it would be shown in Mozambique. I felt a great responsibility, an obligation, to not make mistakes, and above all, to not impose a truth. It happens very often in Mozambique that foreigners come with their films, to show their version of the story, often constructed at a distance, and as a result there are errors that slip in, when, for example, something is added for its beauty or the fascination it exercises, without taking into account the implicit meanings that are inherent to it. Thus the gap present in such works sort of extends colonial history through the idea that foreigners may know better about the situation and history than the Mozambicans themselves. I try to confront this problem by trying to be as specific as possible about the facts, while explaining my own position as a white Portuguese, who makes a film about others. If I stick to my own perception of my work, I feel that I am closer to research than I am to art, at least to the kind of art that is often exhibited today that dwells on the vagueness, the indeterminacy, of archival documents and their interpretation. I try to avoid reproducing my own fascination, and to snatch the images away from exoticism.

SB: For that, you go even more deeply into your material, and much of your work consists of showing the process of understanding. Now, you are not a historian, you work with forms, or through forms. You do not inscribe them in a coherent narrative, but you work with a certain intelligibility of the sensible, and produce a sort of constellation between objects, between your films as well, which you conceive as complementary, as questioning each other, but without providing answers. Again, it is a question of form.

CS: Yes, the question of form is important, especially that of finding an adequate form to present a complex material that questions things rather than gives answers. By situating myself in a non-academic context, I feel much freer to experiment. But I also try to remain flexible, in the sense that I approach other fields of study, such as anthropology. I always try to be as precise as possible, even though what I do afterward is certainly not scientific in the true sense of the word. For example, I work with a group of young independent researchers in Mozambique, Oficina de História (History workshop), which took on the name of a very innovative group that gathered during the independence of Mozambique. This original group thought about how to write a decolonized but committed history, a kind of permanent work in progress. They worked experimentally and collectively—for instance, their texts were written by multiple people. I like this way of sharing knowledge, of helping each other, and of embarking on invention.

First published in

The Fevered Spectres of Art, ed. Nataša Ilić, Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst & Sternberg Press, 2019