Letter to Herman Asselberghs and Pieter Van Bogaert

13 Sep, 22

Brussels, June 2017

Dear Herman, Dear Pieter,

How does cinema think “our time”? Where is the cinema that can take the measure of our present? Those were, I believe, some of the questions you both had in mind when we last met up. Pieter, you recommended to look beyond the conventional manifestations of the so-called seventh art and direct our attention towards the possibilities opened up by new image media, mentioning as a model example the work of Hito Steyerl. You told us that there might be something viable in her explorations of the socio-technological conditions of the “wretched of the screen” and the “post-representational” status of images within the digital world, which is said to be characterized by intensity, velocity, spread and flow. In line with her reasoning, you seemed to imply that cinematic politics might need to go beyond the exhausted tropes of representation and investigate new models of post-production and circulation, which could be employed by post-representative militias and open source insurgents as possible tools towards the demystification and alteration of existing relations of production. To look at what media do, as Steyerl suggests — rather than at what they show.

From your side, Herman, you proposed to take recourse to the potential residing within the bastion of “mainstream” cinema, exemplified by Adam McKay’s The Big Short (2015) which you praised for its ability to communicate complex information about the causes and effects of the 2008 financial crash in a digestible form. With some goodwill, the film could indeed be considered as an updated response to Bertolt Brecht’s quest to blend pleasure and pedagogy, in the guise of a cinematic adaptation of the “true story” of a handful of outsiders who stood up to the titans of Wall Street by capitalizing on what was always clear to see, at least for those who cared to look: the complete fraudulence of the financial system of capitalism that has imposed its logic on our economies and societies. It certainly seems as if Brecht’s famous motto: “What is the crime of robbing a bank compared with the crime of founding a bank?,” [1] has fully broken into the cinematic mainstream, an accomplishment which has inspired some enthusiasts to hail the film as nothing less than Hollywood’s very own “Occupy.” [2]

[1] Quote taken from Bertolt Brecht, The Threepenny Opera (1928).

[2] Jessica Pressler, “The Big Short Will Make You Furious All Over Again About 2008,” Vulture, 30 November 2015.

[3] See Thom Andersen and Noël Burch, Red Hollywood (1996) and Thom Andersen, “Red Hollywood,” in “UnAmerican” Hollywood: politics and Film in the Blacklist Era, eds. Frank Krutnik, Steve Neale, Brian Neve, Peter Stanfield (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 238–241. Thom Andersen and Noël Burch were both guests in the frame of the Figures of Dissent series.

All the while I couldn’t help thinking: what about fiction? I mean, where are the forms of fictional existence that are able to tear themselves away from the dominant modes of illustration and demonstration by which a society is summoned to hold up a mirror to itself? Where are the cinematic worlds that are irreducible to any order of a given reality, with its common sense of what is possible and impossible, plausible and implausible, necessary and contingent? After all, however entertaining and educational The Big Short might be, doesn’t its fable basically operate as a slick blend of a morality tale and a journalistic report, in which a calculated selection of well-recognizable phenomena and enthralling features serves to display the signs of our times? In this case, the main characters, assembled from Michael Lewis’ investigative exposé with the same title, have the merit of functioning both as symptom-bearers, whose traits and manners typify a contemporary way of being, and as examiners who take us for an expeditious ride through the hustle and bustle of the financial market, cleverly identifying and explaining its contraptions and deceptions along the way (notice how many of their exchanges are actually interviews and lectures!). In what can be considered as an overhaul of the well-known fable of mavericks taking on the corrupt establishment, the petty underdogs standing up to the giants of high finance are depicted as finance-savvy geeks and freaks — today’s stereotypes of cool quirkiness and creative expertness — who manage to exploit the flaws of a system which has been blinded by greed by placing their bets against it. In spite of the fact that these audacious investors and fund managers have in reality hugely profited from an economic failure that had harrowing consequences for millions of people, we cannot but sympathize with these misfits whose poorly-socialized personality tics and emphatic back-stories make them appear like either Cassandra figures doomed to witness the forecasted self-destruction of the financial system or ethical crusaders eager to set it ablaze. We cannot but share their skepticism about an entire system that has turned into a painful farce, from the cynical dealmakers of Wall Street and the financial agencies that turn a blind eye to their scams to the lawmakers, the government and the media who fail to interfere. While watching the film I was reminded of a scathing moment in Force of Evil (1948), when the main character, a Wall Street lawyer, tries to justify his complicity in the corrupt banking system to his ill-fated brother: “What do you mean ‘gangsters’? It’s business!” The shortlived era of “Red Hollywood” and the ensuing blacklisting spree might now be long behind us, but Abraham Polonsky’s razor-sharp dissection of the damage inflicted by the organizational consolidation of capital in the aftermath of the Great Depression that followed the 1929 banking crisis seems to resonate more than ever these days. [3] Only now, amidst the so-called “Second Great Contraction” in recent capitalist history, the webwork of bankers, controllers, collectors and runners operating in the twilight zone between the underworld of organized crime and the upper world of official governance have become their salaried professional managerial equivalents in the legitimate business economy, whose culture of greed seems to be beyond reprimand. At the end of his phantasmal descent towards the bottom of the world, the corrupted lawyer in Force of Evil is violently awakened to the evils of a system that drowns all human relationships in the “icy waters of egotistical calculation,” with a sense of deep guilt that topples into a tacit spirit of revolt. In The Big Short, the feeling of guilt that comes with the notional knowledge of the suffering caused by the system’s paroxysm does not prevent the characters from profiting off of it, while at the same time allowing them — particularly one investment maverick who also happens to be haunted by the memory of his brother’s death — to find redemption. When, in the film’s epilogue, we are sardonically reminded that the economic breakdown was followed by a swift return to business as usual and that the institutions that enabled the disaster to happen were essentially rewarded for their failure with huge bonuses and bailouts, paving the way for austerity and growing inequality, who’s not overwhelmed by gut-wrenching sentiments of exasperation and frustration?

[4] Walter Benjamin about his friend’s Threepenny Novel (1934), which he placed in the tradition of the detective fiction as a form of social criticism: “Brecht is concerned with politics: he makes visible the element of crime hidden in every business enterprise.” Walter Benjamin, “Brecht’s Threepenny Novel,” Understanding Brecht, trans. Anna Bostock (London: Verso, 1998), 75-84.

[5] See Robert Pfaller, Interpassivity. The Aesthetics of Delegated Enjoyment (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017).

[6] David Foster Wallace, “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” Review of Contemporary Fiction 13:2 (1993), 151.

[7] David Foster Wallace, “E Unibus Pluram,” 151.

Indeed, it might be precisely the expression and extension of these sentiments that Adam McKay’s film has in common with today’s arsenal of artistic and journalistic works that set out to scrutinize the perversions that are concomitant with the grand capitalist utopia of the market. It would seem Brecht’s mission to “make visible the element of crime hidden in every business enterprise” [4] is once again taken up in full earnest. In line with the Brechtian tradition, The Big Short even winks at the use of Verfremdung strategies in its deployment of fourth-wall dissolving moments and celebrity cameos offering mini-tutorials about derivatives and other financial instruments that pierce through jargon-infused obscurity. Surely, this attention called to the film’s self-conscious cleverness and nobody’s-fool rebelliousness, recalling McKay’s background as a writer for Saturday Night Live, has by now become standard in mainstream satire — in the film factory of Hollywood as well as in the meme factory of 4chan — which seems to ever more rejoice in pointing out the vapidity of every spectacle and the artificiality of every fiction, in front of which every spectator is bound to remain riddled with passivity and frustration. Remember the scene in Martin Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street (2014) in which the main character, setting out to explain the structures of finance, suddenly interrupts himself with a “who gives a shit?” knowing wink to the audience. Our willful ignorance and annoyance in the face of an explanation of the workings of the market is basically performed for us. [5] But is this irreverent signaling of our indifference towards rational expositions and our pathological gravitation towards shallowness supposed to “activate” us, as Brecht and his followers may have believed, or does it merely come down to a cynical ascertainment of our impotence, while at the same time allowing us to congratulate ourselves for getting that the joke’s on us? It’s as if feigned disbelief has become our preferred mode of belief: if we merrily consent to roll with the punches, it’s not because we’re duped, but rather to prove that we’re not! That’s maybe why, in The Big Short, the disposition of a plot whose characters serve to diagnose the symptoms of our time — hardly clashing with the discourse that the world of domination conducts about itself — is strategically counterbalanced with a brand of self-conscious irony that slyly sidesteps the risk of standing accused of overcredulity or naivety; the naivety, that is, to still believe in fairy tales with heroes and happy endings. “I can feel you judging me,” the slickest of the featured traders tells us straight off when we see him receiving his fat bonus check, “but, hey, I never said I was the hero of the story.” It’s as if we hardly need to believe anymore in fiction to submit to it: on the contrary, we only seem to do so to the extent that it offers the possibility to disparage it. Over two decades ago, this “mood of rebellious irony and irreverence” was already identified by David Foster Wallace in fictions that took on a self-congratulating pose of being audacious enough to acknowledge that their own artificial trickery is ludicrous and point out how foolish their spectators are to fall for it. According to Wallace, this ground-clearing strategy could at one time be considered useful in its capacity to reveal a disturbing truth hidden under the cover of common sense, be it that this usefulness rested on the assumption that “diagnosis pointed toward cure, that a revelation of imprisonment led to freedom.” [6] But over time, as the prospect of effective remedies against the sweep of totalizing systems became uncertain, it turned out that the same strategy that was used by self-appointed rebels to expose the enemy with the weapons of critique only served to insulate themselves, holding on to a critical posture while being unable to propose alternatives. Without believable counter-forces to sustain it, how could a reliance on irony and irreverence show itself capable of evoking anything that could displace the hypocrisies and spectacles it debunks? With the truth wide open for all to see, allowing us to incessantly recognize and disavow it, is dismissive knowingness not in peril of settling into what Wallace has called a “cynicism that announces that one knows the score”? [7]

Hence the question that stirs in me: where are the forms of fictional existence that do not merely contribute to the task of diagnosing and debunking the “capitalist realist” state of things, but are capable of drawing out as yet uncharted worlds of shared experience? Perhaps we should follow your intuition, Pieter, and lodge our hopes and dreams in the dark matter of the “post-representational”? The question of fiction, it’s true, has all too often been tied up to the problematic of representation, which is usually regarded as the imperative of verisimilitude and decorum. As a consequence, the concept of fiction has generally come to imply the fabrication of imaginary fantasy worlds which are set in stark opposition to the unadorned fabric of reality. This idée fixe has recently found an echo in David Shields’ often-cited notion of a “reality hunger” that has supposedly effected contemporary art and literature, as it manifests a growing yearning for an experience of the unrehearsed, unsimulated real in response to the tiresome artificiality of contrived plots and fabricated scenarios. The inventions of fiction, Shields claims, are no longer appropriate to deal effectively with what is already an “unbearably manufactured and artificial world.” [8] It is to this theory that Jacques Rancière has responded during our recent conversation in Ghent: “fiction is everywhere,” he stated, “everywhere where a sense of the real must be produced.” [9] Tracing back the Western conception of fiction to Aristotle’s Poetics, he has reminded us that the notion has at the outset not been defined as the mere invention of imaginary and illusory worlds but as a structure of rationality that lends visibility, intelligibility and consistency to a reality that exists outside of it. In contrast to the ubiquitous claim that everything is becoming fiction, he suggests that there is fiction whenever an intelligible structure is proposed which identifies and relates subjects, forms, actions, events and situations in a way that makes sense. The representative mode of fiction that has been dominant since Aristotle — fiction arranged as strategic patterns of causes and effects, ends and means — is merely one possible model of framework to define a shared world of experience, albeit one that continues to underlie the principles of most fictions that aim to make sense of our time by creating credible narratives of social necessity. In that regard, not only writers and filmmakers but also politicians, journalists and critics make use of this model whenever they set out to describe a given situation, explain the reasons behind it and draw consequences from it. We can find it, for example, in the argumentation of a politician who has explained how certain countries are in debt because they have been living beyond their means, an extravagance which can only be regulated by imposing necessary austerity measures; or in the causal connection that a filmmaker has exposed between the conformism of our time and the culture of individualism and self-expression that has detached us from reality, playing right into the hands of the perception managers of our post-truth world. But we can also find this equation of credibility and necessity in the theory that plays off our hunger for the messiness and rawness of the real against the fabrication of artifice, which finds itself grounded in a particular fictional framework that has become well-established throughout the past century, one that threatens to devour all others: that which reduces all phenomena to the reification of our experience, gradually subsuming us to the reign of spectacles and simulacra that have less and less of a relationship to an outside “reality”. This longstanding fiction obviously brings back to the fore what Aristotle railed against in the first place: the Platonic denunciation of the intoxicating and manipulating shadows that keep reality at bay — a denunciation, as we know, that is necessarily founded on a knowledge of the reality that is dissimulated by appearances: to be able to expose the shadows one must already have broken away from the cave where its prisoners are bound by the chains of ignorance and false consciousness. Only now, since the reality that was assumed to be hidden has in many ways become all too apparent, it is revealed that reality itself is dangerously collapsing into a make-believe world, which is manifested in a growing indiscernibility of real and unreal and an undecidability of true and false.

[8] David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (New York: Knopf, 2010).

[9] Jacques Rancière with Stoffel Debuysere (Minard, Ghent, 30 March 2017).

We can find numerous echoes of this powerful theoretical fiction in today’s critical common sense, not in the least in the proposals that encourage us to “withdraw” from representation. When Hito Steyerl, for example, writes that cameras are no longer tools of representation, but tools of disappearance, since “the more people are represented the less is left of them in reality,” [10] doesn’t she also deploy this fictional framework that associates the loss of the real with the entrenched dominion of simulation? Isn’t her likening of digital images to “dangerous devices of capture” [11] that drain away human life, turning us all into free-floaters in a fleeting world of appearances, essentially a reboot of the age-old scenario that denounces the coldness of reproductive machines that threaten to extinguish all human warmth and subjectivity? Isn’t the suspicion towards images and fictions that pour across screens and networks, invading our lives, fully capturing our imagination, attention and productivity, another extension of the Marxist theme of reification? From this widespread interpretation of the evolution of our society, we know that critical art has drawn various conclusions, each delineating a certain set of suitabilities and limitations. On the one hand, art has rooted its politics in the revelation of its hidden structuring aspects and material relations, which are primary to any representational content. The strategy of breaking through the fourth wall that holds up the pretense of dramatic action as reality in its similarity to itself can be seen as belonging to this critical mode. Instead of presenting itself as an imagist creation that is separated from its means of production, art strives to make legible the conditions and procedures that go into its making, as well as the mechanisms that underlie the production and exhibition paradigms that occupy the art field, which Steyerl describes as “site of condensation of the contradictions of capital.” [12] It has, for example, become common by now to point out how the art circuit has become the flagship store of cultural industries, sustained by the hypermobile logic of financial capital, which has taken the initiative to dismantle factories, relocate industries and put old warehouses and breweries at the disposal of art production and exhibition, in order to raise speculation value and reinforce the neoliberal cult of creativity. Taking this critical attitude to its logical deduction, self-styled critical art has unmasked itself as complicit to the structures of exploitation and inequality that it aimed to expose. At this point, the growing awareness of the mirroring of the global financial market in the art market and the limitations of demystifying devices has lead to an appeal for art to practice the change that it preaches and substitute the forms of representation that routinely package situations of injustice and destitution with direct interventions in those situations. In prospect of a re-humanization of societies that have been rendered numb by the capture and deception of fictions and illusions, art has taken on the mission to reclaim its autonomy from “liquefied” institutional structures and market imperatives and re-knit the tangled fabric of the social bond. Reversely, art has also come to embrace “hyper-realist” strategies of over-identification with the market system in view of producing material rather than merely symbolic change. Either way, what remains at work as justificatory argument is the great fiction that reduces every phenomenon and every situation to a symptom of an undeniable truth: that of the totalisation of the world by the logic of capital, which has a way of subsuming everything in its path. In light of that line of argumentation, works of cinematic fiction too tend to be considered as mere reified commodities that participate in mass-market rationality in the service of the industrial entertainment complex, nothing more than “stimulus packages to buy new televisions, home projector systems, and retina display iPads,” [13] determined by material expenditure, big budgets and marketing strategies. “All you see”, Steyerl once said, “is the 35mm film rolling through the camera and wasting all that money.” When all there is to see is the unassailable truth underlying all appearances, then, why watch at all, if not for the sake of critical posture?

[10] Hito Steyerl, “The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation,” The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 168.

[11] Hito Steyerl, “The Spam of the Earth,” 168.

[12] Hito Steyerl, “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post- Democracy”, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin:Sternberg Press, 2013), 99.

[13] Hito Steyerl, “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?” e-flux Journal #49, November 2013.

[14] Clint Burnham, Fredric Jameson and The Wolf of Wall Street (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

[15] Deleuze borrowed the term “experimental night” from Jean-Louis Schefer. Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Athlone Press, 1989), 169.

[16] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Athlone Press, 1989), 60.

In light of the overarching fiction which makes it possible to read in everything the effect of the domination of capitalist reification, it appears that it is not enough to simply experience a film: it has to be interpreted. The association of fiction with the traditional representationalist principles — considering fictions as organic ensembles whose constituent parts are given a functional order in an arrangement of causes and effects and means and ends — has meant that the fictions of cinema tend to be deciphered as taylored expressions of the commodity logic, ostensibly repressing every anomaly to preserve its appearance of consistency. Some critics still try to uphold the possibility of resistance by way of a practice of “symptomatic reading” that seeks to bring to the surface the slippages where the work of fiction breaks down, contradicts itself, stumbles over its inconsistencies. The politics of a fiction is then brought back to its “unconscious,” which can only be identified by delving under its surface in search of what it seeks to repress or omit. This line of interpretation that locates the real meaning of a film beneath its surface level allows, for example, for a reading of The Wolf of Wall Street as a utopian critique of the present, revealing behind the surface depictions of excess, debauchery and misogyny on the margins of Wall Street, the coming into being of a new class: the wolves are actually pirates whose operations constitute nothing less than an enclave of hope. [14] Everything we perceive then turns out to be standing for something else, something that can only be deciphered by way of an interpretative grid that reduces every appearance to a symptom that has to be encoded. What is dispensed with is even the slightest possibility that appearances can produce experiences that escape any kind of grid. Inversely, an opposite tendency shines through in the recent attention dedicated to the “sensory” in cinema, countering the focus on the hermeneutical deciphering of signs by returning to the quest for an art beyond interpretation and representation, an art of the senses that precisely defies assimilation within a common sense perceptual framework. The main point of reference in this quest, as you know, is undoubtedly the work of Gilles Deleuze and his appeal for art to not only break with the world of representation as an “imitation of life,” but also with all forms of consistency that would make its structure intelligible. Against the organic model that governs the representational order, which for Deleuze only imprisons the force of life, he proposes a body without organs, a purely intensive vitality differed by axes and vectors, gradients and thresholds, displacements and migrations, zones of intensities in a continuous process of becoming. What is opposed to the laws of representation is the world that resides beneath it: a molecular world of multiplicities and haecceities, of thought without body or image, undetermined, un-individualized, coming before the very principle of rationality. An a-signifying and undifferentiated world that directly expresses the potentialities of life, which are no longer narratable as arrangements of necessary or credible actions, but awaken the “spiritual automaton” in us through vibrations and affects. Hence Deleuze’s fascination for forms of cinema that spread out what he has called an “experimental night,” forms made up of “dancing seeds” and “luminous dust” that give birth to an “unknown body which we have in the back of our heads, like the unthought in thought, the birth of the visible which is still hidden from view.” [15] In those forms Deleuze detects the possibility of new modes of perception, which he has termed fluid, liquid or gaseous, in which images flow across or under the frame, part of a “matter-flow” that is open to all directions. One of Deleuze’s primary examples to attest to this potential is Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and his theory of the kino-eye, which for him bears witness to the cinematic mission to carry perception back to things, putting perception into matter, making it possible to liberate vision from the coordinates that ground it and relate any point whatsoever in space to any other point. Beneath the order of bodily states, of the relation of cause and effect that characterizes relationships between bodies, cinema is able to institute an open “plane of immanence” where forces of pure intensity, snatched from plots and characters, ceaselessly flow and converge. What is being represented is of little consequence: everything is put at the service of a system of perpetual interaction of particles of matter that are “luminous by themselves without anything illuminating them,” [16] derailing perception from its stable centre and thereby giving rise to a new way of seeing. The work of Vertov par excellence comes to testify to a conception of an image that is not a reproduction of things, but a thing in itself: luminous matter in movement that is not of the world, but that directly forms the world.

[17] See Jacques Rancière ‘’Is There a Deleuzian Aesthetics?,” trans. Radmila Djordjevic, Qui Parle 14:2 (2004): 1-14.

What is at stake is never “reproducing the visible, but rendering visible,” as Paul Klee puts it in a phrase that Deleuze often cites. For Deleuze, cinematic fictions are able to redeem themselves from the laws of representation that subject the world of matter and energy to the order of causes and effects and means and ends, through the virtual conjunction of non-subjectified affects and percepts that constitute the genetic and immanent elements of a new life. However, images understood as pure processes of expressive matter, in defiance of appearances of resemblance and figures of discourse that would have it express a meaning, still need to be represented to give them sense. Here’s where a striking paradox in Deleuze’s theory makes the scene: in his attempt to make manifest the struggle against the world of representation in view of a horizon of total immanence, he actually comes to rely on a description of the struggles of the represented figures themselves. [17] His quest for impersonal forms of individuation seems to lead him back to the actions of characters who are portrayed as both the driving forces and symbolic effigies of this search. In likening the operations of cinema to the operations of its characters, the focus is then again diverted towards the representational givens which come to allegorize the workings of cinema itself.

[18] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What is Philosophy?, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell (New York: Columbia UP, 1994), 176-77.

As if Deleuze can only respond to the quest for an art that aims to project itself beyond representation by making art into something like an allegory of itself. Thus, in Rossellini’s Europa 51, Irene becomes a figure who loses all sense of direction and ventures towards a space that can no longer be anything but the desert of the purely sensible. In Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Jeff’s plastered leg symbolizes the paralysis of action, indicating the crisis of the sensory-motor system. And in Jean Rouch‘s Les Maitres fous the characters engender a process of becoming-other by way of acts of fabulation which, in repudiation of every existing imperial and deterministic narrative, contribute to the invention of a new fraternal people. In the last instance, it turns out that what is really opposed to representation is not the indifferent swirl of particles of matter, but fabulation, as an act of fictional invention that directly conveys the powers of cinema to the fabled people. In the quest for liberation from all forms of totality, befitting a world where faith and confidence in representation are said to have disappeared, Deleuze ends up identifying the inventions of cinema with the forces of life itself. The affects and vibrations that constitute the populations of art turn out to be nothing less than the direct embodiment of the “constantly renewed suffering of men and women, their re-created protestations, their constantly resumed struggle.” [18] The attempt to counter the reification of the molecular world into the schemes of representation leads to the annulation of all distinctions between form and content, aesthetics and politics, in a grand ambience of collective belonging. But, at the same time, the Deleuzian fiction draws us back to the schemes of representation. In his endeavor to suppress all the representative properties in favor of pure material expression, he is forced to draw from the former to give sense to the latter. Everything plays out as if the discourse that hails fictions as compounds of pure percepts and affects, blocs of sensation that cannot be captured by representation and directly identify perceived with perceiver, only makes sense at the price of contradicting itself.

Thinking about this paradoxical to-and-fro friction between the organic and the non-organic, between the sensorial and the discursive, I can’t help being reminded of one of your works, Herman, a video work that avowedly grapples with the state of “our time” and the possibility of resistance: After Empire (2011). In your undertaking to give cinematic existence to Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s notion of the “multitude,” whose contours you saw emerging during the anti-war protests of 15 February 2003, you sought in your own way to establish an antirepresentational statement, one that pitted texture and rhythm against figuration, non-organic life against the organicity of narrative structures, the ungraspable noise of pixilated apparitions against the generic legible images that populate the global spectacle. As radical alternative to reified media forms and instantly readable commonplaces — which you find exemplified by the iconic images of 9/11 — you present us with “images in the process of becoming”, as you call them, inviting us to enter a kind of Deleuzian “smooth space,” a zone of indeterminacy where there are no faces to recognize, characters to identify with or plots to carry us away. In your endeavour to “render the familiar strange,” [19] you end up approaching Mallarmé’s blank page, which you (like Godard) often refer to, as an imageless palimpsest waiting to be filled with new inscriptions. Here action consists exclusively in the continuous movement of errant and itinerant presences appearing, fading, and intermingling on the surface of the screen, allowing them a virtual potentiality that is neither pre-existent nor stable. They correspond to what Steyerl has called “poor images” or “lumpen proletarians in the class society of appearances,” [20] captured with lo-fi cameras or lifted from the infinite repository of the Web, filtered through a mesh of algorithms, dematerialized into bits. The process of dematerialization seems to carry away all form, advancing the powers of chaos against the human figure, who seeks to break free from itself so as to become a body without organs and take flight in the realm of the non-organic. In this world of pre-individual or non-individual singularities, bodies are not represented: they are as if made out of grains, as Deleuze would say. [21] Amidst the moving blur of ghosts of images, awash in a perpetual twilight, we can still discern the visual specters of anonymous protest movements buried under black veneer or the distorted phantoms of an Apple screensaver transformed into a delirium of shapes and colors. But these apparitions are no longer definable by any kind of genealogy or hierarchy: they all fuse into an undifferentiated continuum that is seemingly exempted from the laws of representation. When at a certain moment the notice “Media Offline — Picture” appears, it might recall the way Godard once filled image spaces with the words “usual illustration here,” but the image to fill in hardly stands out: like all other appearances, it dissolves into a homogenous landscape of images that never come into full existence.

[19] Herman Asselberghs in Dieter Roelstraete, ed., Auguste Orts: Correspondence (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010), 37.

[20] Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 32.

[21] “Cinema isn’t theater, rather, it makes bodies out of grains.” Gilles Deleuze, “The Brain Is the Screen,” trans. Melissa McMuhan, Discourse Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998), 47-55. Originally published in Cahiers du cinema 380 (1986).

The oversignification of informational doxa that add up to nothing then finds itself opposed with the a-signification of a flux of hues and tones — or “ambient,” as Pieter once referred to your film — that brings to mind the symbolist vision of sheer music clothing the idea in sensuous form. Isn’t this flow of vaporous images that doesn’t want to identify or state anything in tune with the symbolist model of art, that is: one that works through suggestion and evocation rather than narration? Isn’t this “imageless” art of shapes and colors, stripped — or “evacuated,” as you prefer to say — from the weight of singular bodies embodying thoughts and sentiments, consonant with this “pure milieu of fiction” that Mallarmé wrote about — this particular kind of fiction that operates through a “perpetual allusion without breaking the ice or the mirror,” [22] invoking a sensitivity to the traces of presence whose mystery testifies to the “dark and confused unity of the unseen world”? [23] What strikes me is that this evocation finds an attestation in the echoing monologue intérieur that occupies the soundtrack, amongst a shifting sea of corrosive distortion and washed out tinges, carried by an enigmatic voice that speaks about “phantom shapes and ghost events,” “the ephemeral world of connectivity” and “a love parade” of miscellaneous participants marching as one. “October never comes,” the voice says, but there is another future in the making, a future “after Empire” which is in the hands of the Multitude that holds power, is power. The disembodied voice — whose words we can also read in the book that accompanies the film — does not explain what we see. [24] Instead, it seems to certify the force of what the visual backdrop evokes without ever showing it: the inorganic power that lays behind the world of representation, the music of indistinction seizing all singularities within the same tonality. The vast flux of abstract manifestations that are produced through the action of digital waves and particles appears to find a correspondence in the narrated vision of a new collective body without organs that escapes the stranglehold of Empire. The perpetual metamorphosis of immaterial matter, where images and sounds appear to dissolve into their primal unity, then can be seen as an evocation of what Hardt and Negri term the “plastic and fluid” terrains of Empire, on which the Multitude is in the midst of making itself in a heroic combat to overcome the order that limits its true force. The ambient of mute signs is affirmed as a hymn intoning the becoming of a new collective body, the movement of life itself drawing out the rhythm of an unknown world to come. It is as if the operations of the audiovisual form nurtures the discursive framework that takes its cues from the work of Hardt and Negri, while this framework itself serves as an allegory for these operations. As if the flow of fugitive atoms in the process of becoming, without pre-determined routes or fixed identity contours, can only gain sense through the grid of a frame of intelligibility that relates all things perceptible and tangible to the commonality in which they participate: that of a community possessing the spirit of its material life. Once again, it seems that the more art tends to approach the purely sensible, in which representation is supposed to vanish into a flow of unbound affections and perceptions that are assembling and separating as perpetual vibration, the more it tends to be accompanied by a symbolical or allegorical interpretation.

[22] Stéphane Mallarmé, “Mimique” (1886), in Oeuvres Complètes (Paris: Gallimard, 1998), 310.

[23] Charles Baudelaire, “Correspondances,” Les Fleurs du mal (1857).

[24] Herman Asselberghs and Dieter Lesage, After Empire (Ghent: MER. Paper Kunsthalle, 2013).

[25] Ricciota Canudo, La naissance du sixième art (1911),

[26] Hito Steyerl and Marvin Jordan, “Politics of Post-Representation,” DIS Magazine, accessed May 30, 2017, http://dismagazine.com/disillusioned-2/62143/hito-steyerl-politics-of-post-representation/

[27] Hito Steyerl, “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?,” e-flux Journal #49 (2013).

[28] Hito Steyerl, “The Language of Things,” eipcp.net (2006), accessed May 30, 2017, http://translate.eipcp.net/transversal/0606/steyerl/en.

[29] Hito Steyerl, “The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation,” The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 172

I can see how Hardt and Negri’s theory of the Franciscan communism of the Multitude, implemented through the irresistible power of the global network that is nevertheless capable of exploding the clutches of Empire, has provided an inspiring response to the call for affirmation, at variance with the critical tendencies that keep on lamenting the loss of the real or the grand catastrophe of our present. But isn’t it striking how this fiction that finds hope in the ungovernable currents of energy and creativity circulating through and beyond established social divisions also reintroduces the century-old dreams of new forms of life, blending all that is material and immaterial, conscious and unconscious, art and politics, into a boundless fabric of common sensible experience? Moreover, doesn’t the fascination with the metamorphicity and immateriality of all that is digital bring about echoes of the era when the art of cinema was inscribed in the vision of a new circulation of energy and immaterial matter dissolving the burdens of the old order, when the enthusiasm over the transformative power of electricity chimed with an enthusiasm for the “electrical vibrations of light” produced by the new seventh art? [25] Just recently I could hear another echo of this enthusiastic vision resounding in an interview with Hito Steyerl in which she proposes to “think of the image not as surface but as all the tiny light impulses running through fiber at any one point in time.” By partaking in the circulation of “energy imparted to images by capital”, she says, “people participate in this energy and create it.” [26] According to Steyerl, cinematic tools should no longer be used in the sole service of representation; they ought to be considered as “means of creation, not only of images but also of the world in their wake.” [27] In the era that is considered to be characterized by general intellect and immaterial labor, the dream of Dziga Vertov seems to have gained a new swagger: the exalted dream of “the combined vision of millions of eyes,” replacing the representations and fictions of yesteryear with a symphony of moments and movements that would constitute the sensible fabric of a new common world. This dream of a truly universal language of images and visual bonds that would connect all the workers of the world finds a new incarnation in what Steyerl describes as a “coming common language, which is not rooted in the hypocrite presumption of a unity of humankind, but in a much more general material community.” [28] To engage with these images that are flowing around our networks and traversing our bodies is not a matter of representing but of “presencing”. It is not a matter of picturing reality, but “ripping off large chunks to incorporate it.” In this post-representational vision, the image is no longer thought of as something to identify with, but to participate in, as “a shared ground for action and passion, a zone of traffic between things and intensities.” [29] No longer as a space of mediation, but as a container of energy that is constantly in motion, always being remade, reformatted, rewired. No longer as a form of representation, but as a fragment of the world spreading beyond screens and networks into different states of matter, “a thing like you and me” incarnated as pixilated missiles and hires brands invading the offline and the offscreen.

[30] Hito Steyerl, “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?,” e-flux Journal #49 (2013).

[31] Hito Steyerl, “The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation,” in The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 172.

[32] Julio García Espinosa, “For an imperfect cinema” (1969), trans. Julianne Burton, Jump Cut, no. 20 (1979) 24-26. accessed May 30, 2017, https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC20folder/ImperfectCinema.html.

[33] Jodi Dean, “Images without Viewers,” fotomusuem.ch (2016), accessed May 30, 2017, https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/ still-searching/articles/26418_images_without_viewers

Affirmation at a time when “there is no more outside”, following the demise of the old aspirations of class struggle and the redefinition of labour, is thus found in the emergence of a distributed network of common creativity engendered by the cognitive artist-workers of the Post-Fordist era — “Today, almost everyone is an artist,” [30] writes Steyerl — in which artistic creation and mechanical reproduction become intertwined; an emergence that is presented as a demonstration of the connection between two essential theses of the Communist Manifesto: all that is solid dissolves into air, and capitalism will eventually dig its own grave. In line with the vision of a productive multitude that grows within the bounds of Empire, the erstwhile call of Walter Benjamin to liberate the tools of cultural production from the claws of capitalism in order to realize their emancipatory potential finds itself updated in the idea of a new form of positive “barbarism” that is at work in the immaterial, intellectual and communicative processes that shape our globalized world of production. In his time Benjamin particularly put his confidence in the potential of cinema, whose role he considered as similar to that of Brecht’s Epic Theatre: to encourage a form of learning that hinges on observing, playing and discussing; a form that would give spectators access to the meanings hidden under the surface of the perceivable and encourage them to seize the means and products of mass technology for themselves. Since the experience and tools of cinema were becoming available for everybody, claimed Benjamin, the distinction between actor and spectator, consumer and producer, was about to lose its validity, which would surely play a role in the upsurge of class consciousness. Hence Benjamin’s admiration for the work of Vertov and other Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s, who not only cast aside star actors by replacing them with “extras” who were asked to portray themselves, but also advocated a demystification of film technology by bringing it closer to the audience. In this way spectators could become artist-engineers, whose mission consisted of replacing the images of yesterday with “things” that enter directly into production in common, which is the production of common life. It is this aspiration of using the means of cinema to participate in a collective mode of productive existence, rather than to produce commodified products for the consumption of passive onlookers or the enjoyment of Bourgeois aesthetes, that seems to be given a new cachet in the work of Steyerl. To the extent that “people are increasingly makers of images — and not their objects or subjects,” she writes, “they are perhaps also increasingly aware that the people might happen by jointly making an image and not by being represented in one.” [31] For her, the models of cooperation and circulation made possible by the ubiquitousness of digital production and network technologies respond to the promise of an “imperfect cinema” as described by Juan García Espinosa in his 1969 manifesto. [32] Today, Steyerl suggest, this promise of an alternative audiovisual economy and ecology that accentuates playful creativity rather than artistic mastery, open-ended process rather than narrative closure, active participation rather than passive contemplation, has taken the form of a decentralized and global circulation of anonymous “poor images” that are constantly in motion, available for anyone to appropriate, modify and recombine into a multiplicity of variations that compose a new symphony. The force of this ever-evolving symphony is not based on the representative capacity of images but on their circulatory power, to the extent that they have become “images without viewers” that freely flow into our life montage, [33] images that are no longer validated for their originality, quality or legibility but as material realities themselves, within which we are deemed to participate.

If art is asked to withdraw from representation, it is no longer to break the illusion of consistency and wholeness and point out the reality behind appearances – as in the Brechtian logic — but to participate in a global, non-hierarchical “circulationism” in which the boundaries between reality and appearance have evaporated. Acknowledging that there is no more outside, no more distance, Steyerl suggest that it is only by participating in this circulationism that we can live productively with the streams of images that surround and threaten to overflow us, these unending streams that are characteristic of the condition that is said to define our contemporary historical moment: the condition of “liquidity”. In her video installation Liquidity Inc. (2014), she attempts to testify to this condition by drawing upon the polysemy of the liquidity metaphor to weave analogies between liquefied financial flows and weather patterns, between the fluidity of labor markets and the flux of algorithmic trading, between the fluctuations induced by corporatization and the fluids of corporality, between the circulation of capital and the migration of people. Footage relating the story of Jacob Wood, a Vietnam-born Wall Street investment banker who became a Mixed Martial Arts professional after the bursting of the housing bubble, morphs into staged weather reports delivered by meteorologists in balaclavas against a green screen showing flashing tumblr images of Hokusai’s The Great Wave and maps of trade winds and data clouds. An auto-tuned mantra of Bruce Lee uttering that “Water can flow or it can crash” echoes with snapshots of floods and tsunamis inlaid into iPhones or television screens, which are interchanged with images showing Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus and interest rate graphs, while members of a variant on The Weather Underground warn us about the storms blowing people back to their homes and back into the past. Backed by the bubbly polyrhythms of Arthur Russell’s “Let’s Go Swimming!”, images portraying the hybrid fighters of MMA flash by while Jacob Wood’s remarks on the growing demand for adaptability and flexibility merge with the words of a financial expert explaining the necessity to build up liquidity in order to avoid disaster. A series of popping up Messenger windows display a multiplicity of conversations in which the artist communicates with her globally dispersed accomplices about the austerity measures which have left her on the verge of a nervous breakdown, while a digital animation shows human figures drowning. Corporate graphics, CGI animations, text messages, clipart pictures and art historical blips float across various screens as matter in motion, mutating, intersecting, looping, morphing into a fluid continuum of digital mash-up whose form seems to match its content.

This hyperlinking of heterogeneous elements in a seamless expanse of co-belonging might faintly bring to mind the Vertovian constructivist undertaking to compose diverse gestures, actions and activities into an indissoluble organic whole, amounting to a great egalitarian communist symphony. Only here the commonality that is asserted through the arrangement of disparate entities, which are readily betraying their allegiance to the reign of artifice, is that of the “liquidity incorporated” that runs through our networks, screens, eyes and veins. While Vertov’s attempt to affirm the living reality of Communism relied on a performative montage that rendered fragmented movements and patterns derived from all strands of life together into in common rhythm, here a sense of commonality seems to be created solely on the basis of analogy and homonymy. From the omnipresent animations of water to the liquefied design of text and the discourses on the fluidity of labor and capital; while Vertov sought to express the global movement of a new life by tearing images from their representative order and bringing into play the dynamism of their movements, Liquidity Inc. articulates an interrelatedness of seemingly disparate flows by drawing upon wordplays, double-entendres and conceptual correspondences between various visual, auditive and discursive elements which find their common denominator in the idea of liquidity. The lexical ambiguity of water becomes a semantic rhizome through which Steyerl’s fiction knots and furls, evocative of a world in which “everything flows,” from the global unregulated flux of financial speculation and the torrential circulations of digital imagery to our amorphous subjectivities swimming in the endless depthless river of capital. Paradoxically, just like Deleuze demonstrated the invention of liquid images through the manifestation of images of liquid, Steyerl’s appeal to “become water” and actively disperse into the postrepresentational flux where object and subject dissolve into one another, is given sense by relying on elements that indexically, iconically or symbolically represent water. In other words, the demonstration of the liquefaction of everything, to the ruins of representation, rests solely on the conceptual sense of images rather than on their affective force. Moreover, the call for participation in the undifferentiated circulation of poor images ends up differentiating itself in the same spaces that it opposes: in the sanctuaries devoted to “auratic” art, where its manifestations are exhibited in high definition quality and imbedded in specially designed environments, where they are more often than not accompanied by wall texts where we find written the affirmation of its concept. Once more, it is as if the logic of anti-representation, pushed to the point of undecidability, can only be given sense by drawing from what it rejects.

[34] For an extensive analysis, see Jacques Rancière, “Seeing Things Through Things (Moscow, 1926),” Aisthesis: Scenes From the Aesthetic Regime of Art, trans. Zakir Paul (New York: Verso, 2013), 225-243.

[35] Viktor Shklovsky saw Chaplin as an exemplar of his concept of “ostranienie,” the operation of art that allowed for the transformation of something familiar into an experience of perceiving it for first time. Viktor Shklovsky, Literature and Cinematography (1922), trans. Irina Masinovsky (Champaign, IL: The Dalkey Archive Press, 2008).

So it appears that today’s urge to withdraw from representation stirs up quite some echoes from cinema’s childhood, when a scepticism towards the conventions of the representative order coincided with a call for art to do away with mediating distance altogether, inspiring both the symbolist dreams of an imageless art that could directly realize ideas in material form and the Soviet program that identified the operations of cinema with the energies of a world in flux. But those who continue to oppose the organic consistency of representative fiction with the fluidity of images that are either commonly dissolved in a cloud of luminous matter or brought down to the common identity of particles that are infinitely malleable, transformable and recombinable into new arrangements, seem to bypass a tension that lies at the heart of cinema: the tension that exists between the movement of sensible forms open to transformation and the deployment of semblances in a rational arrangement. In a way, Man with a Movie Camera epitomizes the utopian aspiration that this tension has awakened: the quest for a performative form of cinematic movement that connects all other movements, configured in an impersonal dance of atoms that does not differentiate between the motion of productive energies and the semblances of society. But ultimately this quest for a free movement of matter can not be fulfilled: every shot in Vertov’s films finds itself pointing back to the omnipresent representations of the all-seeing camera-apparatus, of its operator with his camera-eye and the editor with her cutting machine who master the visible and give direction to the choreography of movements and intensities. And we shouldn’t forget that the film begins and ends in the film theatre where we see its images being shown to the actors themselves, who are supposed to overcome the division between art and life and participate in the construction of a new world. In giving prominence to their faces gazing in reverie at the screen, the symphony of movements intent on mobilizing energies seems to highlight its own contradiction. It is only by refraining to linger on what is given to see, or by plainly refusing to look, that the cinema-machine can be unequivocally identified as an undiscerning transmitter of pure energy waves that call on participation and interaction —- which is exactly what finds symbolical expression in the film’s recurrent images of a telephone transmission network, connecting a tangle of activities and actions into a grand symphony of interweaving melodies. [34] It’s this irresolvable search for cinematic forms that are grounded in the pure power of movement, rather than in the traditional causal logic of representation, that also animates the response to the work of Charlie Chaplin, that great admirer of Vertov who created the epitome of international working-class humanity with the figure of the Tramp. If his films were a major source of inspiration for those who wished to celebrate cinema as a new art capable of adapting to the rhythms of the new world, it’s because its dynamisms could be identified with the dream of creating a universal art of movement that could not be brought back to the fabrication of sentimental stories or the mere concatenation of autonomous images. In light of this dream, Chaplin could be acknowledged as a master choreographer who managed to break with the conventions of theatre by composing a play of pure forms and automatic movements, which for some commentators epitomized art’s operation of “ostranenie” or defamiliarization. [35]

[36] For an extensive analysis, see Jacques Rancière, “The Machine and Its Shadow (Hollywood, 1916),” Aisthesis: Scenes From the Aesthetic Regime of Art, trans. Zakir Paul (New York: Verso, 2013), 191-206.

At the same time, he could also be praised for his capacity to efface himself from his creation, to disappear in his own body which he stripped of all expressiveness and psychology. But what makes the operations of the eccentric figure of the little fellow with the bowler hat and cane so resonant might not simply be his paring down to the outlines of a popular archetype or to the basic mechanisms of an automaton, but rather his astounding paradoxical performance that continuously turns into its opposite, at the same time based on an automatisation of gestures and giving rise to surges of emphatic emotion. And this performance is only possible due to a fictional framework that makes the actions of the Tramp as committed to swift inventiveness and machine-like precision as they are vulnerable to contingency and failure. For all his mechanical performativity and repetitive behaviour, there’s always the unforeseen and the errant peeping around the corner. For all his passion for orderliness, there’s always his innate rejection of authority. How many times have we seen him, when confronted with the violence of the world, erupting into contorted violations of the established order before readapting his imperturbable figure and burlesque mask when confronted with a representative of this same order? Without ever exposing the reasons for his actions or drawing any consequence from them, the adventures of the Tramp unfold as a perpetual swirl of transformations where things metamorphose endlessly, constantly alternating between movement and suspension, order and disorder. [36] In such a way, he can perhaps be seen as another incarnation of the street magician that Vertov self-consciously integrated in Man with a Movie Camera: the illusionist performing a series of singular metamorphoses that bring about a multiplicity of displacements and reversals that expresses nothing but the field of its own possibility. And isn’t this precisely what is all too easily set aside by today’s hailers of post-representation: this game of metamorphoses which allows cinema to exceed its plots and concepts?

[37] Slavoj Žižek on the website of Criterion, accessed May 30, 2017, http://www.openculture.com/2015/01/slavoj-zizek-names-hisfavorite-films-from-the-criterion-collection.html

[38] Aaron Schuster, “Comedy in Times of Austerity,” in Ivana Novak, Jela Krečič, Mladen Dolar, eds., Lubitsch can’t wait (Ljubljana: Kinoteka, Slovenian Cinematheque, 2014), 29.

With the advent of the talkie, around the same time as the economic crisis erupted in the US and the work of both Vertov and Chaplin started to fall out of favor in the USSR, cinema stopped being the flag bearer of anti-representative art, but that didn’t put a halt to the cinematic play of transformations. Instead, it found its way into the old art of storytelling, where it continued to join traces from popular forms of entertainment— vaudeville, circus, pantomime — with sparks of the mechanical dream. I’m thinking of a remarkable comedy of manners I watched the other day, one that, like The Big Short, deals with the relation between property and theft by putting on show a charade of illicit trades and exchanges. The film has recently made its grand reappearance after being lauded by the likes of Slavoj Žižek, who called it “the best critique of capitalism,” [37] and Aaron Schuster, who described it as “perhaps the ultimate comedy for times of austerity.” [38] I’m referring to Trouble in Paradise (1932), one of the first American ventures into sound film by Ernst Lubitsch, who took his friend Chaplin’s A Woman in Paris (1923) as a model to create his own brand of marivaudage set among the posh and wealthy.

[39] Aaron Schuster, “Comedy in Times of Austerity,” 32.

[40] Jacques Rancière, “La porte du paradis,” Cahiers du cinéma, n° 554 (2001).

[41] Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp,” Partisan Review, Fall (1964), 515-530.

[42] This observation can also be found in François Truffaut, ”Lubitsch Was A Prince” (1968), The Films in My Life, trans. Leonard Mayhew (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978), 162-172.

If this film offers a portrait of our times, writes Schuster, it is because it shows the spectacle of a world where “everyone is stealing, and no one is punished.” [39] Somewhat redolent of the favorite themes of fellow Hollywood émigré Brecht, the plot sketches out how self-made tricksters and imposters pretending to be upper-class types steal from the wealthy who cynically let their own stealing be organized by the ruling system of exploitation and accumulation. The lavish spectacle that Lubitsch has devised is a sarabande of deceivers and deceived, seducers and seduced, who constantly change masks and make their way through opening and closing doors leading to destinies we are left to imagine. It is this game of doors that has been alluded to by Jacques Rancière in reference to a particular scene in which we get to see the sole revolutionary in the film — scolding a rich heiress for indulging in wealth at a time of crisis— make a short entrance before being thrown out the door. [40] It’s as if Lubitsch meant to stress that cinema has no need for a demonstration of the truth that is hidden behind appearances, no need for a mirror in which onlookers are bound to recognize the realities of life. After all, isn’t cinema itself a marvelous piece of fraud, as fervent Lubitsch-admirer Godard once suggested — an art of imitation and impersonation that thrives on a game of appearances, offering a world of shadows where the real and the illusory can freely exchange assets and liabilities? Many have remarked that one encounters in the work of Lubitsch, fascinated as this tailor’s son was with sensuous surfaces and frivolous textures, an emphasis on style and artifice that comes at the expense of content and narrative, leading Susan Sontag to famously count Trouble in Paradise “among the greatest Camp movies ever made.” [41] It is indeed striking that the phrase “in times like these,” which runs like a refrain throughout the film, never does more than suggest the Great Depression that engulfed the capitalist world in the 1930s. The outside reality of precarity and inequality seems to leave the film, just like its main characters, completely indifferent. The entrance of the raving champion of class struggle can therefore only be short-lived: the dissident, along with any critical demonstrations of the misery and injustice underlying the character’s follies and vices, has to be put at the door, removed from sight, for the marvelous performance of swindle and seduction to take its course. What drives the film is not the confrontation between deception and the truth that unmasks it, but rather it is the dramaturgy of derivations, bifurcations and inversions that constantly upsets the relation between what is expected and what is visible, between words and their effectiveness. Lubitsch doesn’t offer us a fiction based on connections of cause and effect, quite the opposite: he only introduces causes or effects the better to displace or contradict them. [42] Telling a story doesn’t interest Lubitsch half as much as the play of exchanges and interactions whereby the theft of a pocketbook equals the stealing of one’s heart: the swindler’s words of deceit are at the same time expressions of love and the victim’s intimations of naivety are at the same time gestures of complicity. Awareness of the pretense and make-believe doesn’t stand in the way of seduction, on the contrary: it allows us to fully savor the pirouette of words that say something other than what they appear to say and the trade-off between the real and the illusory that unremittingly switch places. According to Rancière, the force of this world of appearances is precisely sustained by the evidence of the world of conflict lingering outside: as long as the naked truth of the class struggle roared behind the door, there could exist some kind of solidarity between the magician of illusion and the guardian of truth. The ambiguous web of appearances crafted by the first could just as well be identified by the latter as a symptom of the unreproved bourgeois propensity to drown all social relations in the icy waters of egotistical calculation and the indifference of capitalist equivalence. But what happens with this dialectical relation between social reality and cinematographic appearance when the guarded truth underlying appearances is known to anyone and the movement of history that guaranteed the traversal of appearances is suspected of being an appearance itself?

When the history of domination can no longer be taken for a world of appearances doomed to dissipate to the benefit of the naked reality of class struggle, the argument is no longer that appearances conceal secrets which are no longer secret to anyone but rather that nothing at all remains hidden anymore. I believe it’s this critical common sense which allows Žižek to explain the contemporaneity of Lubitsch’s work by calling him “the poet of cynical wisdom,” who acknowledges that society is held together by semblances which we shouldn’t take for real while secretly continuing to transgress them in the interest of pleasure. The fictional game of appearances and the derangements of the relation between reality and illusion in Lubitsch’s work then turns out to attest to the truth of our time, which finds expression in a phrase that Kafka penned down a century ago: “the lie made into the rule of the world.” [43] But the crumbling of the theoretical scenarios that made it possible to diagnose the intolerability of the injustices produced by the dominant order, and the identifiable movements that reacted against it in practice, has also resulted in a growing suspicion of mimetic artifice. Rather than fictions, that is to say rational arrangements of actions, events and situations that principally owe no explanation for the truth of what they show, cinema is considered to be made up purely of simulacra, which cannot but remove what is represented from its weight of existence. With its supposed causal link to awareness and action severed, the representation of the intolerable then collapses into the intolerability of representation. We can think back to the violent reactions directed at Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942), which have both been retrospectively criticized for their inappropriate representation of the Nazi regime and the figure of Hitler. The mixing of fancy and fact, of farce and disaster, for the sake of entertainment was considered incompatible with the gravity of the reality it referred to. In contrast to Godard, who has presented the films of Chaplin and Lubitsch as illustrations of cinema’s announcement of the impending catastrophe before renouncing its responsibility to bear witness to reality and subsuming to commodification, these critical arguments reject the right of cinema to integrate and assess even the most overbearing realities in its fictions. One of the most well-known criticisms undoubtedly comes from Theodor Adorno, who has chastised The Great Dictator for its trivialization of the experience of the horrors of the Nazi period. [44] Strangely enough, Adorno has on other occasions described the “constellation animal/fool/clown” as “a fundamental layer of art,” lauding Chaplin’s clown-figure for its primitive mimetic energy in which he found a renunciation of all that belongs to the “purposeful grown-up life… and indeed the principle of reason itself.” [45] In a sense, Adorno could have just as well evaluated The Great Dictator in the same way that he had appraised the earlier work of Chaplin, but at this particular point in time, tainted by the memory of destruction and suffering and an increasing suspicion towards the reification of consciousness imposed by dream factories, he chose to condemn the film for its indignity and profanity. In light of reality at its grimmest, the chain of metamorphoses between the Tramp, the barber, Hynkel, Hitler and eventually Chaplin himself — at the high cost of sacrificing the iconic figure of the Tramp — where we don’t exactly know who is who and who imitates who, is responded to with an denunciation of mimesis altogether. At a time of disappointment over the failure of the proposed wedding of art and life and a waning confidence in the transformative power of images, Adorno became one of the most outspoken detractors of cinema’s reproductive realism, in particular when he found its semblance of immediacy amplified by the introduction of sound, which he felt left no more room for imagination or reflection on the part of the spectators, who find themselves forced to equate representation directly with reality. By exploiting its mimetic qualities and tailoring them for maximum efficiency, cinema was considered as an instrument of the totalizing regime of domination which applied its “fairy-tale glow” to accustom the audience to its brutalities, to the extent that “reality becomes its own ideology through the spell cast by its faithful duplication” and “the image turns into immediate reality.” [46] With cinema understood as the flagship of the coercive and commodified forms of cultural mass reproduction, turning man into a subject and the world into an image, it became common to regard the traversing of the borders between art and non-art and reality and illusion as highly suspect. Following that logic of suspicion, it would only be a matter of time before the warnings against the elimination of the gulf separating art from life would mutate into the by now all too familiar declaration that art, now undone from its power of illusion, has morphed everywhere to become embedded into everyday life. “Nowadays,” Hito Steyerl writes, ”the invasion of art is not the exception, but the rule” while the area of art itself has “incorporated all that it broke from.” [47] With art exposed as no different from anything else and real life deemed indistinguishable from the movies, [48] hasn’t it become all too easy to cast aside cinema’s fictional operations, those alterations and transformations that makes the art of cinema a privileged site for exploring the relationship between the order of the real and the appeal of fairy-tales?

[43] Slavoj Žižek, “Lubitsch, the Poet of Cynical Wisdom?,” Ivana Novak, Jela Krečič, Mladen Dolar, eds., Lubitsch can’t wait (Ljubljana: Kinoteka, Slovenian Cinematheque, 2014), 181-205.

[44] Theodor Adorno, “Commitment” (1962), in Aesthetics and Politics, ed. Ronald Taylor, trans. Francis McDonagh (London: Verso, 1977), 184.

[45] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (1970), Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, eds., trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (London:Bloomsbury, 2013), 165.

[46] Theodor Adorno, “The Schema of Mass Culture” (1942), trans. Nicholas Walker, in The Culture Industry: Selected Essayson Mass Culture, ed. J. M. Bernstein (London: Routledge, 1991), 55.

[47] Hito Steyerl, “Art as Occupation: Claims for an Autonomy of Life,” The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 172.

[48] “Real life is indistinguishable from the movies”, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer asserted in “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” from Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944). An echo can be heard in this quote from Hito Steyerl: “We used to believe that fiction is the reflection of something that happened in reality, which was then exaggerated and embellished. But now we see everywhere fictions becoming real. Fictions are like architectural blueprints to create reality because people try to imitate fiction and they try to repeat it, live up to it or embody it, and then they get it wrong and then a new story starts. “Hito Steyerl and Andrey Shental, “In the Junkyard of Wrecked Fictions,” Mute (2013), accessed May 30, 2017, http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/junkyard-wrecked-fictions.

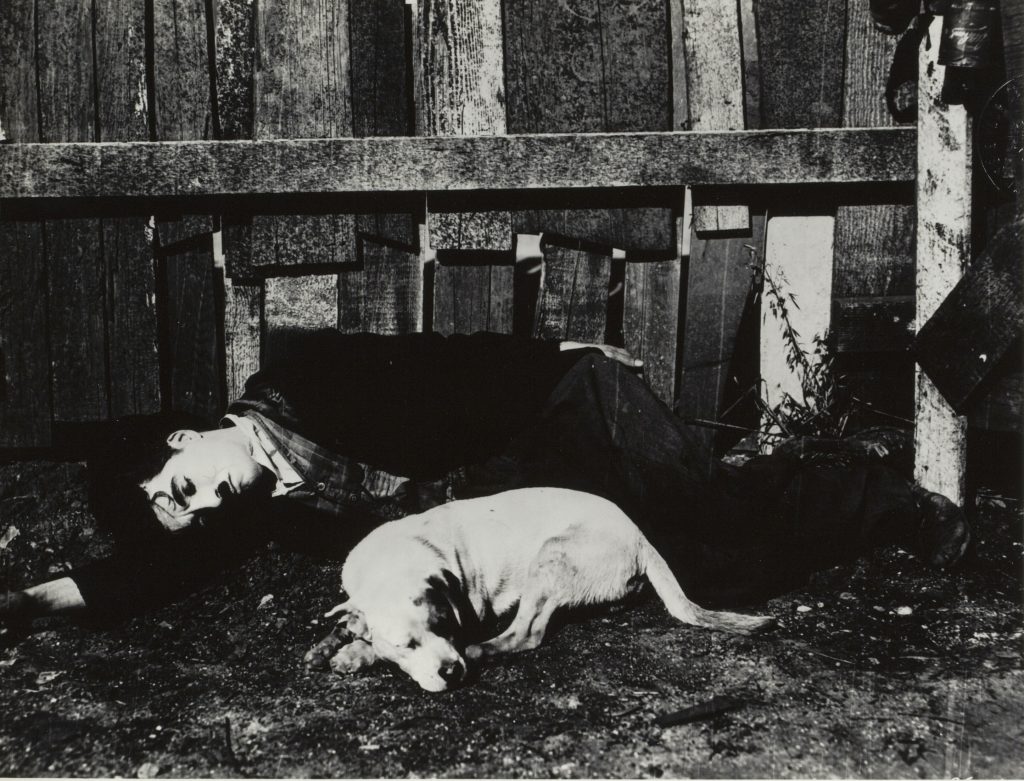

In light of those changed sensibilities towards the relation between the appearances of cinema and the demands of the real world, Chaplin and Lubitsch’s fictional play of metamorphoses that draws its force from its subtraction from the exterior weight of the real no longer seems to measure up to the requirements of “our time.” Instead, we often find ourselves in front of mirrors in which mimesis is reduced to a display of identities, attitudes and signs that invites us to recognize the real of the social imaginary, or otherwise we are taken up by calculated panoplies of haptic affects or “panic-images” denying recognition in favor of a sensory experience of immediacy. [49] And having grown weary of pathos or sentimentality, we have come to prefer the gratification granted by the deconstruction of the lure or the clever game with codes, showing that we are not taken in lightly by the tricks of illusionists. To all appearances, in a world where the borders of social division can no longer be symbolized, the capacity of the marauders of yesteryear to turn around every situation has altered into an inaptitude to thwart or overturn any position altogether. The alienation of factory life and the mobilization of workers that animates the Tramp in Modern Times (1936) have virtually disappeared from view in the contemporary Western world of financial capitalism and delocalized material production, where collective spaces for conflicting forces are becoming rarer by the day and the commonality of the workplace is superseded by the individual management of flexi-jobs and “human capital.” Without the reality of work as a common world and a collective force of struggle, without dissenting figures plausible enough to embody the truth of social violence, cinematic bodies often seem to float in mid-air, at loss for words that could set them in motion or actions that could turn things around. How many of our contemporary fictions do we find populated by solitary mute bodies with faces expressing the inexpressive and movements suspended in time, struggling to strike a resonance with a sense of commonality? In an attempt to challenge the all too familiar fictional forms based on functional situations and well-ordered sentiments, while at the same time reclaiming the pure enchantment of cinematic appearances, many of these fictions seem intent on autonomizing the force of immobility that is inherent to the movement of images. It’s what I see, for example, in the work of one of the filmmakers I discussed with Rancière that afternoon: Kelly Reichardt. If the companionship of a vagabond and a dog in Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (2008) reminds us of Chaplin’s A Dog’s Life (1918), it also highlights the immobility of its world, where stealing a piece of food in a time of crisis no longer erupts into a clash with police officers who act as the preeminent guardians of class division, but only affirms and deepens the spiral of social exclusion and isolation, which does no longer seem to allow for fictional transgressions. Instead the suspension of movement of the irretrievably broken down car that prompts Wendy’s drift seems to spill over into the whole film. The perturbing body of the little fellow living hand-to-mouth and scrambling for survival against all odds, bearing witness to the violence of the world while simultaneously making it into a game, has become a wandering figure who circulates from one furtive chance encounter to another without being able to transform anything. She too doesn’t fit in with the established order, but the organized anarchy that the force of the Tramp was able to wreak upon that order, as rigorous as it was pointless, has been cancelled out, while his ludic capacity to take over any identity has been petrified in the identity of the “outcast,” fallen by the wayside and relegated to the margins of society. Reichardt herself has described her films as “just glimpses of people passing through.” [50] In Deleuzian fashion, we could also describe the situations of the young woman stranded in small-town Oregon in search for her lost dog as “pure optical and sound situations” in which the character does not know how to adequately respond and becomes instead a witness to time passing. [51] Bereft of immediate direction, she sets out on a “stationary voyage” through the “any-space-whatever” of a former industrial town that has yielded to wear and ennui, a world riddled with blandness and fleetingness where a sense of lasting connection can apparently only be found in the companionship of animals. The heartbreaking moment when Wendy finally finds Lucy but decides to leave her behind where she can still be taken care of also brings back the film to its starting point, to the suburban train yard where the presence of hobos and vagabonds conjures up images of the Great Depression. When we get to hear the whistling of the train that Wendy leaves on, it does not resound anything like the call of the wild but rather like an echo from a half remembered past when the great departure could possibly still look forward to a horizon of change.

[49] The term “panic-images” was proposed by Georges Didi-Huberman in his account of László Nemes’ Son of Saul (2015). Georges Didi-Huberman, Sortir du Noir (Les Éditions de Minuit, 2015).

[50] Kelly Reichardt and Xan Brooks,: “My films are just glimpses of people passing through,” The Guardian, 21 August 2014, accessed May 30, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/aug/21/-sp-kelly-reichardt-my-films-are-just-glimpses-of-peoplepassing-through

[51] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Athlone Press, 1985)